Haitians possess an indomitable spirit. They can make something from nothing. To meet them is to fall in love with a place and a people. In the year before the earthquake, they seemed to have finally turned a corner. Twenty-five years of turmoil followed the fall of both Duvaliers. During this time, life folded into an endless succession of strikes and protests; barricades and mass demonstrations; coups and counter coups; juntas; lootings; disappearances; AIDS, malaria, and TB epidemics; 80 percent illiteracy; 60 percent unemployment; environmental catastrophes; and Duvalierist puppet masters parading as democrats. Finally, after all that, Haitians saw a hopeful future under devoted and sometimes competent leadership. These images are part of a long-term essay about the poorest country in the western hemisphere. They recall a time of hope, bravery, the horrible price people pay for something we take for granted, people crushed by dictatorship, briefly tasting democracy, slipping into anarchy, and then appearing to overcome all obstacles. Once the rubble is cleared, will the same scenes repeat themselves? Will redemption follow Armageddon?

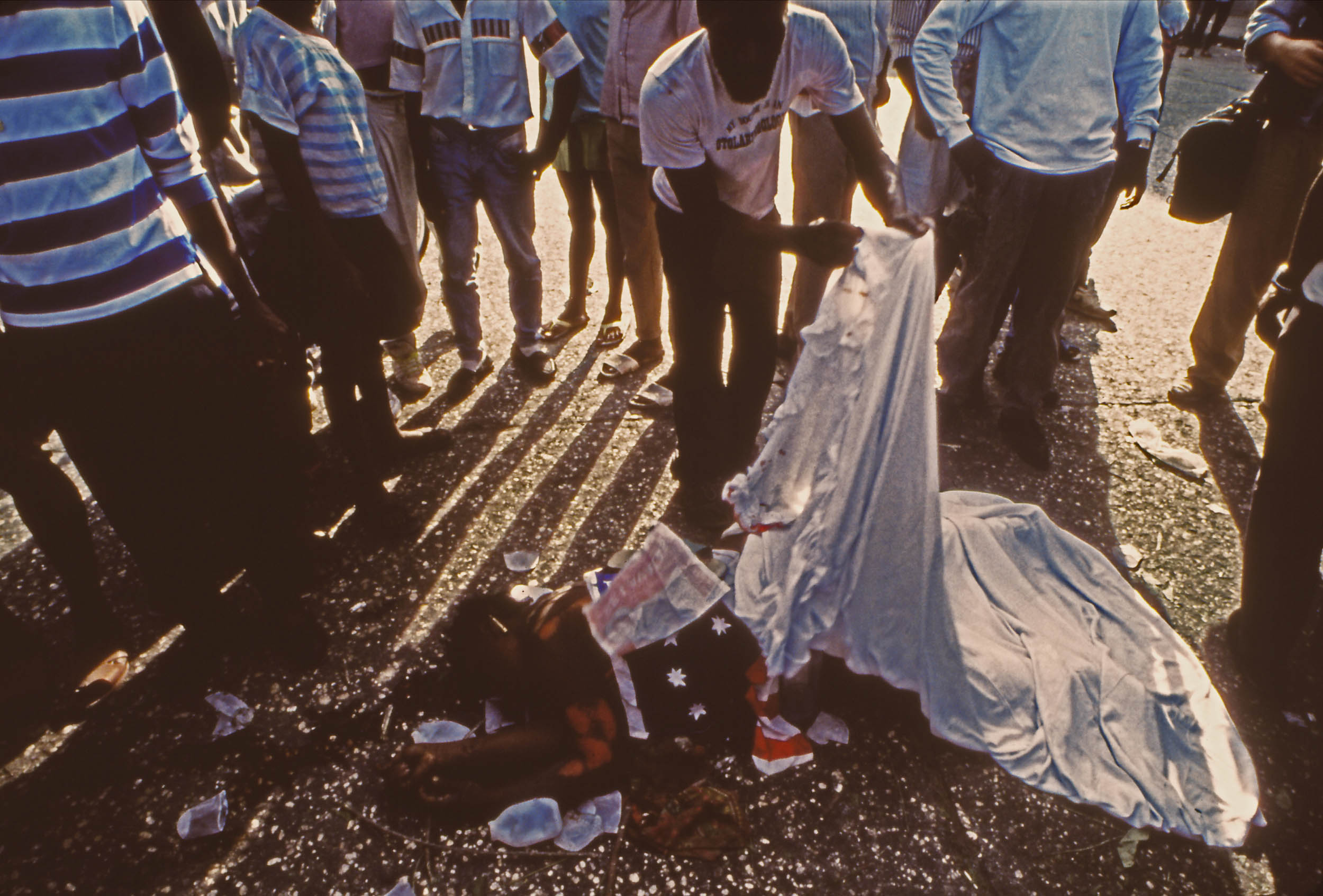

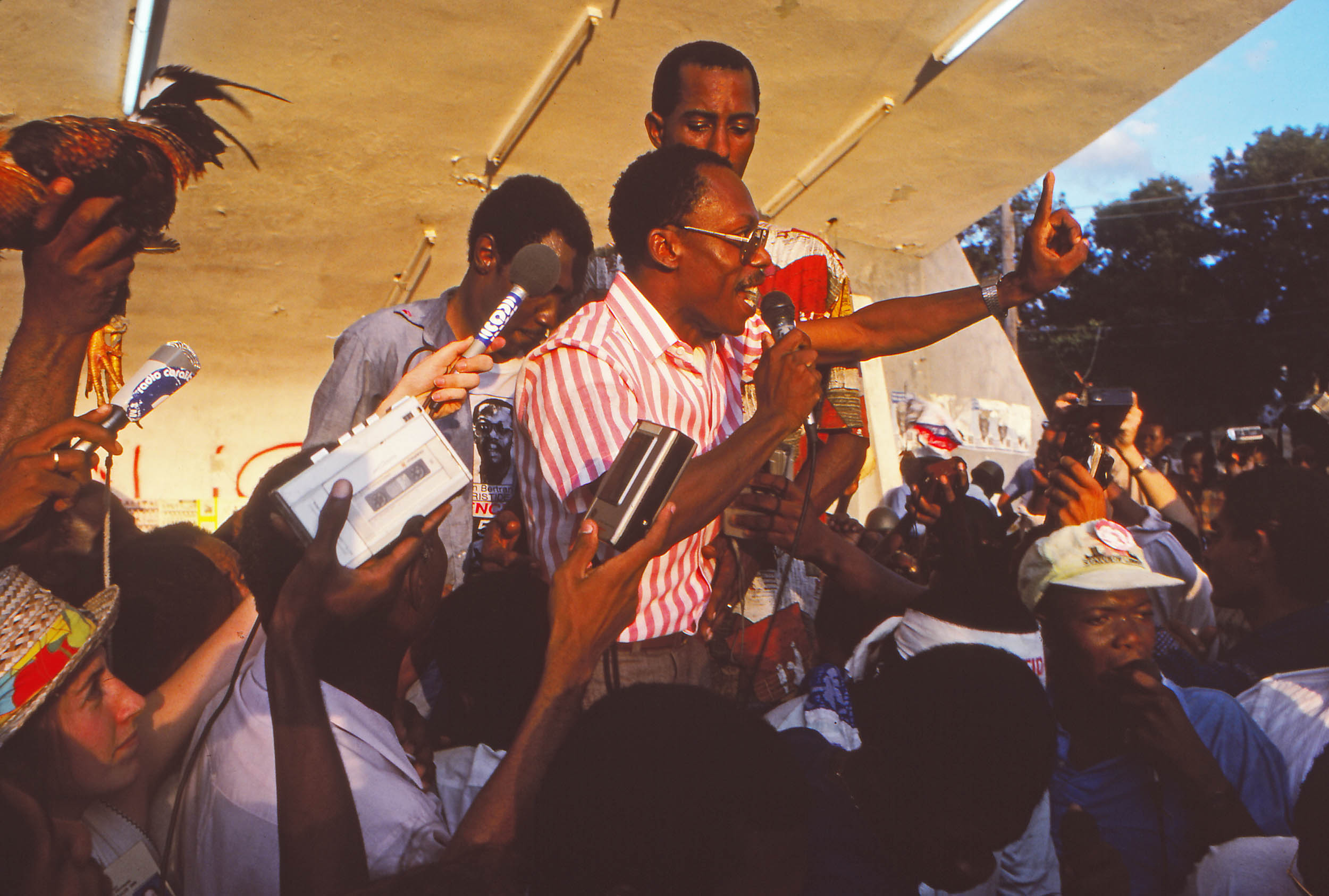

I first visited Haiti in 1987 to cover the country's first democratic elections. On November 29, gunmen massacred voters and reporters, women and children, entire families, assembled at Ecole Nationale Argentine Bellegarde, a polling place on Ruelle Vaillant, in Port-au-Prince. Everyone fled over walls embedded with broken glass. Journalists and photographers scattered along Avenue John Brown, where Jeffrey Lite, an American Embassy presse liaison, scooped them into a bullet-proof vehicle. Back at the Holiday Inn, where we had holed up, a report of Tontons Macoutes (a murderous, state-supported Haitian Gestapo) lurking outside sent us smashing out a restaurant window and onto the roof. A few days later Macoutes murdered the devout, stabbed pregnant women, and nearly hacked up photojournalist Maggie Steber while she documented Father Jean Bertrand Aristide celebrating mass at St.-Jean-Bosco, a tiny Catholic church on Grande Rue. Journalist Amy Wilentz would return to the scene of the Ecole Argentine massacre, look at the lakes of blood and tributaries of brains, shoes and bags, school kids in blue uniforms and web-like rivlets of God-knows what, and see in them an abstract map of Haiti. "Marred by violence" -- the euphemism newspapers used to describe events - barely grazed the hackings, burnings, decapitations, and assassinations comprising the blood bath and terror that killed elections. This essay attempts to overcome our tendency toward cowboy journalism and historical amnesia by connecting past and present and placing the current catastrophe within the context of Haiti's ongoing struggle.